Summary

Low-lying coastal communities are increasingly confronted by recurrent flooding due to sea level rise (SLR). The tidal cycle now takes place on higher average sea levels, resulting in “sunny-day” flooding during high tides. As sea water infiltrates stormwater drainage systems during normal tidal cycles, ordinary rainstorms can cause flash floods. While coastal adaptation planning has largely focused on the risks from major storm surge, chronic flooding from SLR poses a new threat.

Since 2021, the research team has been collaborating with the town of Carolina Beach, North Carolina, a small town already struggling with the impacts of sea level rise. The PIs deployed custom sensors in key flood-prone areas of the town in early 2022. In the first year of data collection, we detected 45 floods (where a flood is defined as standing water on the roadway). The town government triggers flood monitoring based on the forecasted tide height. Fully 30% of the floods we detected were completely unexpected: the forecasted tide was below the monitoring threshold, but due to non-tidal forces and land-based drivers, the streets flooded nonetheless. Our ongoing work in other communities suggests that this problem is widespread: it is flooding much more often than indicated by existing data sources, and communities are grappling with the immediate impacts (flooded roads, impaired wastewater systems) and long-term consequences with little data to inform their choices.

Our ongoing collaboration with the town has been highly productive to date. Using our custom sensors and cameras, we collect water levels and photographs from three of the most flood-prone areas in town. The data and photos are shared in real-time via our website, which town staff use to monitor roadway conditions and manage access. We have also used the data to validate a detailed flood model for the town, which incorporates stormwater drainage infrastructure as well as the effects of land-based and ocean-based flood drivers. In Year 9, we began engaging community members and town officials to identify and evaluate adaptation strategies. This effort includes deploying a survey to all town residents and property owners to assess flood impacts and adaptation preferences, using the flood model to evaluate the effectiveness of adaptation strategies, and convening a working group of community members and officials to discuss model results and prioritize adaptation options.

In Year 10, we will expand our efforts to improve the useability of our data and research products and develop transferable best practices in communicating about these frequent, smaller-scale floods. This work is motivated by our continued engagement in Carolina Beach and elsewhere in North Carolina, which has revealed new questions of interest to our end-users and challenges with our current science communication efforts. For example, town staff recently asked us about how to use the data to assess whether backflow prevention devices (part of their stormwater infrastructure) were functioning as intended. We have gotten informal feedback from community members that they do regularly refer to the website, but also that it can be difficult to navigate and tell whether it is likely to flood soon.

Chronic coastal flooding has several unique features that make it difficult to communicate and distinguish from other types of floods. Unlike storms, they are not generally life-threatening, and there is little if any public warning through local news or radio as would occur with a major storm. They occur often, which means people may become desensitized to any warning they do receive. Nonetheless, reducing the impacts of chronic floods does require that people know and respond to them, for instance by avoiding flooded roads, timing their trip to avoid the highest tide, or even moving trash cans that would be upended by the water. Understanding how to communicate effectively about these events is a necessary first step for mitigating their impacts.

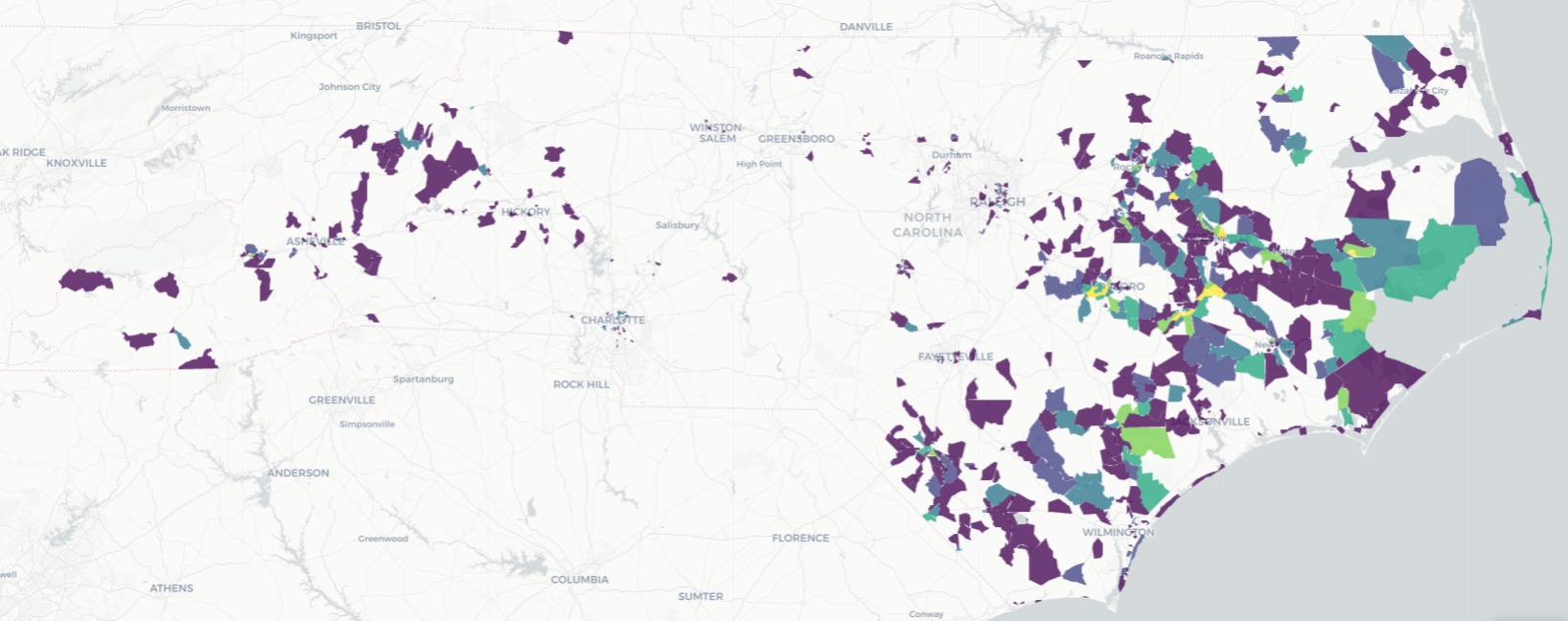

To improve the useability of our data and research products, we will 1) analyze the information needs of our various end user groups, 2) develop new science communication products (data viewer, flood alerts, website) to meet those needs, and 3) pilot test and evaluate the effectiveness of those revamped products. We will expand our engagement in Year 10 beyond Carolina Beach, analyzing end user needs within other partner communities in North Carolina as well as at the state and federal levels. The goal of this work is to develop transferable products and lessons about communicating about chronic flooding that can be deployed more broadly, given that so many communities in the US face similar challenges.

Investigators

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

NC State University